Today’s a day that many of us will remember for a long time.

Today is the day that Donald Trump was elected to be the 45th President of the United States.

His election has caused a lot of people, me included, to feel rather gloomy about what lies in store for us over the coming years.

Certainly the values he espoused during his campaign were not ones that I feel any kind of affinity with.

I’m no great fan of aid as a solution to the World’s problems but, whatever its motives, the United States has been one of the most prolific donors of aid to Africa in recent decades. If Trump’s election rhetoric translates into US foreign policy this may well change.

So what lies ahead for the people who have come to depend on that aid?

Could this become an opportunity for us to do things in a better way?

I’ve been involved with Africa for over 30 years and with conservation for the past 15.

Wildlife conservation is a contentious subject and although there are many organisations and individuals out there who share the goal of saving endangered species, they are often at each others throats about how that might be achieved.

For me it is largely a matter of common sense.

Whatever approach we take, it must be sustainable

It cannot be considered sustainable if it is entirely dependent on westerners donating money.

Nor can it be sustainable if it is based upon Americans and Europeans telling Africans how they should manage wildlife that they have lived in relative harmony with for hundreds (thousands?) of years.

Humans and wildlife are in conflict for Africa’s space and resources.

Most wildlife reserves have been established by evicting local people and tribes from the land they have traditionally occupied.

Though these wildlife reserves and National Parks are designated as sanctuaries for the animals they are nonetheless still limited in area; restricting the animals from moving freely from one area to another in search of food and water when they need to. And surrounding them are human settlements, in many cases populated by the very people evicted to make way for the reserve.

When people are evicted from land they consider their traditional home and told that they can no longer farm and hunt there because it has been set aside for wildlife, it is easy to understand their resentment. Especially if they then get no benefit from the revenues that are generated.

It doesn’t have to be that way

Community led Conservation

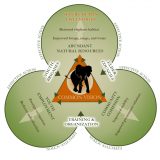

The only way that conservation can be sustainable is if the people who are affected by it, the people who must co-exist side by side with the wildlife, gain benefit from it and are therefore motivated to support it.

There are some inspiring examples of how this has been put in to practice.

There are many advantages to the community-based management approach adopted by CAMPFIRE:

- Communal lands can act as game corridors between existing National Parks, protecting the genetic diversity of wild species

- It creates jobs – local people are trained and become involved as environmental educators, game scouts etc

- It prompts environmental education and promotes the benefits of wildlife conservation to communities

- It provides an incentive for people to conserve wild species

- It generates funds, which are used for community projects or to supplement household incomes

- It creates more revenues for wildlife management and conservation projects in areas that would otherwise not receive adequate financial support for conservation

In order to advance CAMPFIRE conservation efforts, further technical assistance will be needed by rural communities. They would also benefit from secure land tenure and rights over their wildlife. In addition, the ability of CAMPFIRE to assist wildlife conservation in Zimbabwe depends on several wider factors:

- The acceptance of hunting as a wildlife management tool by the international community

- Placing economic value on wild species

- Exploring different ways of realising that value, such as through wildlife tourism, trophy hunting and game ranching

source: The CAMPFIRE website

Yet, even initiatives like this are not enough.

Food insecurity is one of the biggest problems facing Africa

Despite having 60% of the World’s arable land, the continent cannot feed itself

Right now, smallholder and subsistence farmers are producing an average yield of 1.1 tons of maize per hectare; they need to produce 2.7 tons per hectare to feed themselves and their dependents.

That is a shortfall of almost 60%!

Just as conservation must be sustainable to have any chance of success, so must agriculture.

No matter how well intentioned, aid hand-outs are just a sticking plaster that mask the symptoms. Not only do they do nothing to tackle the causes but they are considered by many people to actually be a fundamental cause of Africa’s poor farming practices.

The current situation cannot be allowed to continue.

Africa is home to 1.2 billion (up from just 477 million in 1980), Africa is projected by the United Nations Population Division to see a slight acceleration of annual population growth in the immediate future.

In the past year the population of the African continent grew by 30 million. By the year 2050, annual increases will exceed 42 million people per year and total population will have doubled to 2.4 billion, according to the UN. This comes to 3.5 million more people per month, or 80 additional people per minute.

Aid is not the solution

Aid donations cannot keep pace with this kind of growth, nor should they have to. Africa must get to the stage where it can feed its people.

Generations of poor farming practices are being compounded by climate change, declining rainfall and a failure to adopt a sustainable approach.

If people are starving, wondering where their next meal is coming from, how can we expect them to be enthusiastic about saving the wildlife?

From their perspective, those animals are using land that they could be using to grow food or graze livestock and competing for scarce water resources.

In the past they would have been seen as a food source, but now to hunt them is illegal.

If we can give these smallholder farmers the means to make better use of the resources available to them and grow more food and remove the spectre of starvation, then we might be able to engage with them about wildlife conservation.

“Developing Africa’s breadbaskets depends on improving the productivity, profitability and sustainability of smallholder farmers. This army of small producers – the majority of them women – grows most of Africa’s food. And they do so with limited government support, minimal resources, poor quality seeds and a lack of fertilizer to improve the quality of their soil. They also now have to cope with the emerging impacts of climate change.”

“Empowered, smallholder farmers can lift their communities out of poverty and help make Africa the world’s breadbasket.”

Kofi Annan, UN Secretary General 1997 – 2006